Saturday 26th November

At 1400h GMT we left the Melville Seamount (38 deg 28' S, 46 deg 45' E) to begin our transit to the "Dragon Vent Field" on the SW Indian Ridge (37 deg 47' S, 49 deg 39' E). Voyage 67 of the RRS James Cook is now officially underway.

When we arrive at the vent field, we will have 72 hours to survey the vents, map the distribution of life around them, and collect specimens of species to compare with those at other vents elsewhere in the oceans.

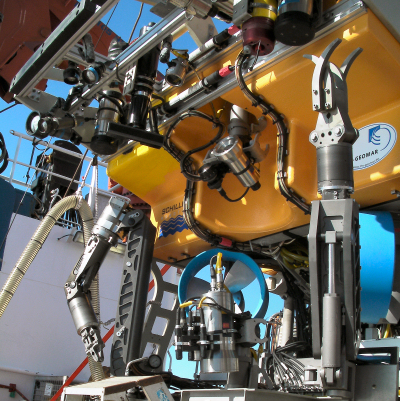

We will be working at a depth of 2.7 kilometres, and it will take the ROV two hours to reach the seafloor, and two hours to return from it. So our bottom time during a dive lasting 10 to 12 hours each day will be limited to 6 to 8 hours. We will therefore be using the ROV primarily to collect samples, and measure the distribution of life on vent chimneys using a high-definition video system and the ROV's precision position-control capabilities.

At night, when the ROV is on deck, we will switch to using the HyBIS vehicle. HyBIS is not primarily designed for collecting biological samples from vents (although she did us proud in the Cayman Trough), so we will use her to map the locations of all the chimneys of the vent field, and survey other areas nearby where there could be more vents.

It's an exciting but tense time as we approach the vent field. There's excitement at the prospect of seeing these vent chimneys and their inhabitants for the first time, and thereby learning more about the distribution of marine life in the deep ocean. But there is tension from the tight timeline for our work: we can only spend 72 hours at the vents, before the ship must move on to keep its schedule for other projects. So every minute will count, or rather must be made to count in gathering samples and data.

The "science" part of being a deep-sea scientist - using appropriate methods to collect samples and data, and analysing and interpreting them - is only one part of the job. Out here, success also depends on the different teams aboard ship working together effectively - the bridge officers, deck crew, expedition technicians, science team, and ROV team. The role of Principal Scientist at sea is to be the "glue" that helps to make that happen, and two-way communication is the key.

Fortunately I'm supported on this trip by our team member Leigh, who is both "right hand" and "devil's advocate". Leigh's role is to share the running of the show around the clock, spot anything missed in plans, and examine the thinking behind decisions to make sure that the right ones are being made.

Two of the biggest potential threats to our work are weather and technical problems. Fortunately the weather forecast looks promising for the next few days. Encountering technical problems with equipment can seem frustrating, but is routine when working at sea, and we rely on the ingenuity of our technicians to provide alternatives. Consequently we rarely get to execute "Plan A" at sea - or even "Plan B" or "C". I don't expect the next three days to prove any different.

Our estimated time of arrival at the vent field is 0100 GMT tomorrow morning. It has been 28 months since writing and submitting the research proposal to investigate these vents, and now we are just hours away.